A Peer at Homecoming:

Migrants Start Home Curriculum Schools For Displace Learners

Written by: Hellen Kabahukya. Photography by Moses Sserunjogi

Written by: Hellen Kabahukya. Photography by Moses Sserunjogi

It’s 7:30 am, Dalal Muhammed is just on time for her first class that starts at 8:00am. It’s a routine she has had for the last 6 months, traveling about 11 kms from Naalya to Kabalagala, both distant suburbs in Uganda’s capital Kampala.

Muhammed, 18, is in Senior Four, majoring in science at Ark International, a school set up to cater exclusively for South Sudanese students living in Uganda. Her dream is to be a Pharmacist and hopefully get a job back in Sudan.

“This is my final year before I join university. My only purpose is to work hard and get a scholarship to pursue pharmacy at a good university.” Muhammed says excitedly.

She was forced out of school in April 2023 by armed conflict. For over 9 months her family had to start over from a new state till they were ready to move to Uganda for a more permanent solution.

Upon arrival, a Ugandan education system dictated that she had to go a few classes behind let alone taking a separate class on English Language.

“The schools we visited required that I go back 2 classes behind and some suggested I start all over. It wasn’t fair and I honestly couldn’t accept it,” Muhammed explained.

In Sudan education, the mode of instruction is in Arabic, this meant that she needed a school that understood not only Arabic but the Sudanese grading method and the education curriculum.

“We struggled finding a school because Ugandan schools were not able to know how to grade me for my rightful class. Luckily, I found Ark International” Muhammed explains

Muhammed Dalal attends class at Ark International School in Kampala. Photo by Hellen Kabahukya.

A true Ark.

The scrolls of the old have alluded that when God warned of the flood that would wipe out humanity he sent a man Noah to build an Ark. The ark was meant to preserve life, a life that would be fundamental in building the new generation.

When the floods came, true to the warnings, the ark was able to preserve every animal and human.

Ark International School though not akin to the scriptures built their school to preserve the education system for the South Sudanese and offer an opportunity to students to complete their education from where they left off back at home.

With a sitting center in Nimule on the border of South Sudan and Uganda, they opened up a school in Kabalagala, a suburb in Kampala, well known as a settlement magnet for most urban refugees.

“Our sitting school is in South Sudan at the border but we opened up this branch and one in Kenya because we realized that many south sudanese were struggling to integrate the education system of other countries especially Uganda,” Milton Yuma the headteacher explains.

In Kampala the school officially opened in January and has enrolled over 30 students from Sudan and South Sudan. The school offers a holistic environment with an 8-5 timeframe where the students engage with a very intensive timetable.

“At the end of the day they are going to be graded the same as the students in South Sudan, so we ensure that they are well equipped. So you’ll find that at every end of a unit, what you can call a topic, we test them to see how much they have understood,” Asianzu Ganga Winfred

A teacher at the school explains.

When the school put out its adverts on social media, it received many applications for various reasons but for most, it was a chance to complete school using a curriculum they were familiar with.

“I came to Uganda to finish my secondary school but was forced to start again and it really affected me given my age. This school gives me an opportunity I thought I had missed,” Tutdel Lam, a student at Ark International.

The civil war in Sudan, has caused a highly complex displacement crisis that has forced more than 8.6 million people to flee their homes since April 15, 2023.

Reports indicate that the conflict has forced the closure of over 10,400 schools, predominantly in the restive regions, leaving 19 million children without access to education.

The destruction of universities and schools across the country, as well as the forced migration of staff and students, have led to a complete standstill in the education system of both countries

“Many of my friends had to move to safe states in Sudan but fear to enroll for school just in case they are attacked again,” Muhammed tearfully explained, adding that for many of them drop out or find alternatives away from formal education.

In South Sudan,Nearly one in every three schools in conflict-affected areas has been destroyed, damaged, occupied or closed. Over 400,000 children have been forced out of school due the ongoing conflicts

Children often have long and dangerous journeys to attend classes notwithstanding other barriers like early marriage, educational costs, overcrowded classrooms, and untrained teachers are keeping kids out of school.

Uganda hosts over 1.5 million refugees and 47,000 asylum seekers and of that number over 100,000 refugees live in Urban areas.

South Sudanese makeup 57% of the total number of refugees in Uganda with 65% being under the age of 18, a school going age for children in Uganda.

While Uganda is open to supporting refugees in the country, its systems dictate that the students from these countries alter their system to be accommodated.

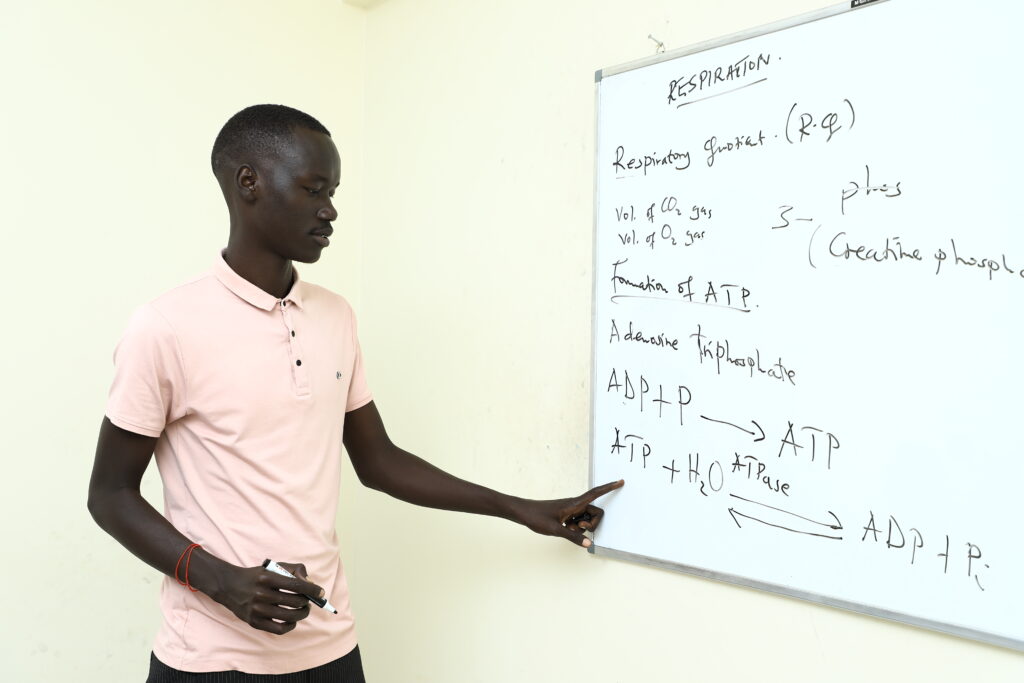

A teacher delivers a science class at the Ark International School. Photo by Hellen Kabahukya.

The Difference

The education system in South Sudan relates to the Republic of Sudan. Though with related subjects and courses it differs with that of Uganda.

Basic school consists of eight years and secondary, followed by four years and then four years of university. However, in the post-independence period, South Sudan decided on two official languages of instruction including Arabic and English.

On September 8, 2015, the South Sudan Ministry of Education and Sports launched the first comprehensive national education curriculum.

Prior to the launch of the national curriculum, there were no complete or comprehensive curriculums in South Sudan. Some schools were using the South Sudan curriculum while others were using curricula from Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan, or a hybrid depending on what resources were available and could vary by state.

“In Secondary 1-2, the required subjects include Religious, Citizenship, History, and Geography and in Secondary 3-4, the required subjects include Religious and Citizenship Education, making most of the core subjects in Uganda optional in our curriculum,” Yumi explains.

In Uganda however, a grade 1-4 student at secondary level would do about 12-14 subjects only reducing those to 10 at grade 3-4.

“In the first two levels, the south and North Sudan curriculum covers what is covered till level 4 in Uganda, and the last two levels cover what we call Senior 4 is what in Uganda is considered Senior 6” Milton the headteacher of Ark international elaborates.

This would mean a child enrolling in a continuing program in Uganda from South Sudan would have to start again given the disparity of core subjects.

“So our curriculum has more subjects that are different from the Ugandan syllabus. We have subjects curated to suit our country’s environment and needs,” Asianzu explains.

The curriculum in south sudan is critical to the needs of the country and thus their education is critical to the opportunities available.

Students pictured in class at the Ark International School. Photo by Hellen Kabahukya.

Not a new development

In 2019, Complexe Scolaire audie du ciel School (Equal in Heaven) was founded to help foster education for congolese migrants in Uganda. Similarly Complex Scolaire Katwe was founded in 2016 with the same goal.

The vision was to help foster reintegration for Congolese students who were forced to stop their education mid way.

The challenges of Congolese are similar to South Sudanese.

“The Congolese curriculum is in French and when students come here they have to start all over again despite having been ahead back in Congo.” Kasereka Seth, the headteacher of Complex Scolaire explains.

Many of the migrants hope to return home and make a difference in their country and this education works in their favor as they do not struggle to reintegrate when they return back home.

“The curriculum we apply is rooted in our history, systems, and we teach what works for our country just like Ugandans have their own systems that work for the country. This will help our students apply the knowledge when they go back home,” explains Habiragi Nyange, the headteacher of Complexe Scolaire Du Ciel.

At the end of the school program just like the south sudanese school, the students are transported back to Congo to sit for national exams usually in schools along the Congo-Uganda border.

While the work of these schools can transform the future of migrants in the country, the struggle comes in with financing where most migrants are unable to afford the education and are forced to drop out altogether.

“ Away from the struggles of money, our students have to travel from long distances that are very costly and tiresome. The option of hostels is also not feasible as it only increases the costs for the already struggling parents,” Yumi explains.

The other challenge is the language barrier at higher institutions in Uganda.

“We teach in french here at complex but then when it comes to university education we don’t have accommodative higher institutions of learning in Uganda, which means that the students either enroll for english classes outside the school or return to Congo for university which at at times is not safe for them,” Nyange explains.

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .