Thriving together:

Community School Pioneers Sustainable Learning Model for Children With Special Needs

Written by: Rhonet Atwiine. Film and Photography: Richard Mugambe, Moses Sserunjogi.

Written by: Rhonet Atwiine. Film and Photography: Richard Mugambe, Moses Sserunjogi.

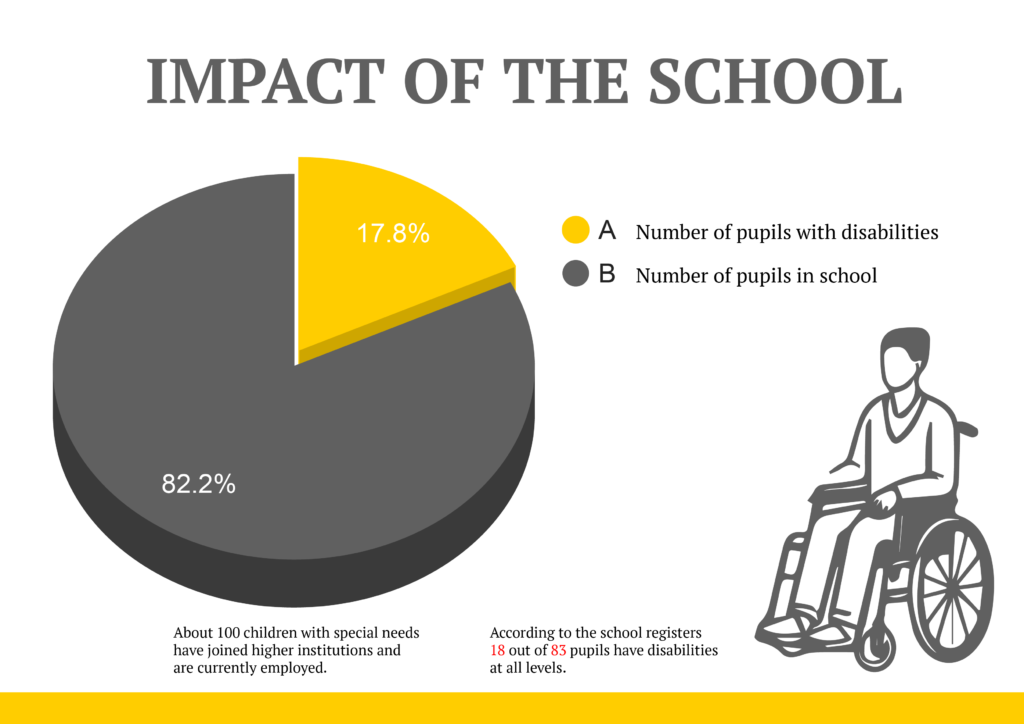

At Wisdom Hub Nursery and Primary School, two in every five of its close to 100-learner population has some form of disability.

The school, a private social enterprise in the community of Katende, in Mpigi district about 40 kilometers outside Uganda’s capital Kampala is one of its kind in the country where discriminatory social beliefs hold back children with special needs from going to school.

Anna Nasirundi enrolled her now eight-year-old daughter at the school in 2022. The child, born with partial paralysis, had been withheld from learning.

“We thought she could never read or write. However, I felt that my child deserved the same opportunities as any other child,” she said, adding that “I wanted my daughter to be capable of navigating life on her own.”

Anna Nasirundi shares with Solutions Now Africa about how her child has improved at Wisdom Hub school. Photo by Moses Sserunjogi.

The child has been a quick learner and has passed well to join primary two. She is dreaming to be a future doctor.

This school uses what it terms as “I do, we do, you do model” which entails collectively working on learning tasks, then later progressing into individual work.

According to Agness Ninsiima, a teacher of Mathematics, who has been personally close to Nasirundi’s child, the model creates more time and attention for a special needs child from the teacher to fellow learners.

“As a teacher, I begin by demonstrating an activity on the blackboard, ensuring that all students can follow along. Then, we collectively engage in the activity, with a student taking the lead. Finally, I assign the task for pupils to complete independently, ensuring active participation from every child.” she elaborates.

A World Bank special needs factsheet suggests that about 16% of children in the country have a form of disability. However, most of them are not able to attend school, while those who attend fail to transition from one educational level to another.

Whereas the Ministry of Education and Sports says all the 21,000 schools in Uganda practice inclusive education by admitting learners, only 5 percent of children with disabilities can access education through Inclusive Schools, and 10% through special schools

Children play together during a classroom break at Wisdom Hub School. Photo by Moses Sserunjogi.

Solutions Now Africa conducted research among stakeholders of inclusive education – children with disabilities, parents and guardians, community groups, local schools, students, and teachers – through a survey and on-site interviews in Kampala Metropolitan in Uganda from July to August 2024.

The survey results gathered from 50 respondents revealed that 72% of people have a child in their family or community with a disability and lack access to education in their communities.

In addition, the survey indicated that negative attitudes and stigma, physical capacity, infrastructure, learning materials, and inadequate teacher capacity impede children with disability from attending school.

According to Sarah Bugoosi, the Commissioner for Special Needs and Inclusive Education at the Ministry of Education and Sports, all schools in Uganda should be inclusive but there are fewer resources available to achieve it.

“We want all schools to be inclusive, but we do not have it all. We are talking about schools not having enough teachers and salaries. So if the teachers for children without disabilities are not enough, what do you think we are going to do at the end of the day?,” says Bugoosi.

However, she explains that the government is making attempts at newer measures and programs tailored to support students with diverse learning needs.

“To curb this gap, we have established schools that accommodate children with disabilities as we find a way to better inclusive education. So far, we have 23 special needs schools for both primary and secondary, and about 50 integrated schools all over the country. But we are also looking at making other inclusive schools in time to come,” Bugoosi explains.

Whereas the commissioner highlights the existing proposals, the slow attempt by government to prioritize equitable access to education speaks to the national dilemma.

In addition, the ministry has also made an effort to support children with special needs and ensure that even they have access to learning materials like magnifiers, braille machines and papers, and other technologies used by special needs students.

Despite these efforts, numerous challenges persist in implementing this policy, and at the center of this is budgetary constraints. This causes a decline in allocation and stagnation in funding to programmes which limits interventions aimed at inclusive education.

Such programs include funding salaries for special needs teachers, putting up infrastructures that support children with special needs, and buying enough learning materials that support the education process of children with special needs.

“We have so many professional special needs teachers out there but schools can not afford them because they demand a high pay compared to others. In addition, learning materials are very expensive, for example, a visually impaired child needs a braille machine and paper. But a machine alone is at UGX 3.5 million and a paper at UGX 35,0000, That is only a book and a pen for a term or a year,” Bugoosi explains.

Children pause for a photo moment outside the classroom. Photo by Moses Sserunjogi.

With challenges for the government to prioritize funding for effective teaching and learning for students with special needs, Uganda’s education sector has been greatly supplemented by private players.

However, for learners with special needs, private entities trail as much as public schools in creating inclusive learning environments.

“Many private schools struggle to include children with disabilities, fearing financial repercussions. Also, some parents resist their children learning alongside those with special needs,” says Moses Walusimbi explaining why he started the Wisdom Hub Primary School.

Bugoosi explains that in inclusive education settings, the learning pace tends to be slower, and more attention is required for special needs children, which can result in less overall learning for the entire class.

However, she attributes this to the inability of schools to plan for children with special needs at the initial stages, therefore, trying to accommodate them at later stages becomes expensive for the school and parents.

“Imagine having to build lamps, recruit sign language teachers, buy braille and other learning materials for 1 to 10 children with special needs! It is very costly, and this only means that parents will pay higher school fees than others. But there are schools with all these facilities and children have been able to survive, the problem is that they are very few compared to the learners with special needs,” she explains.

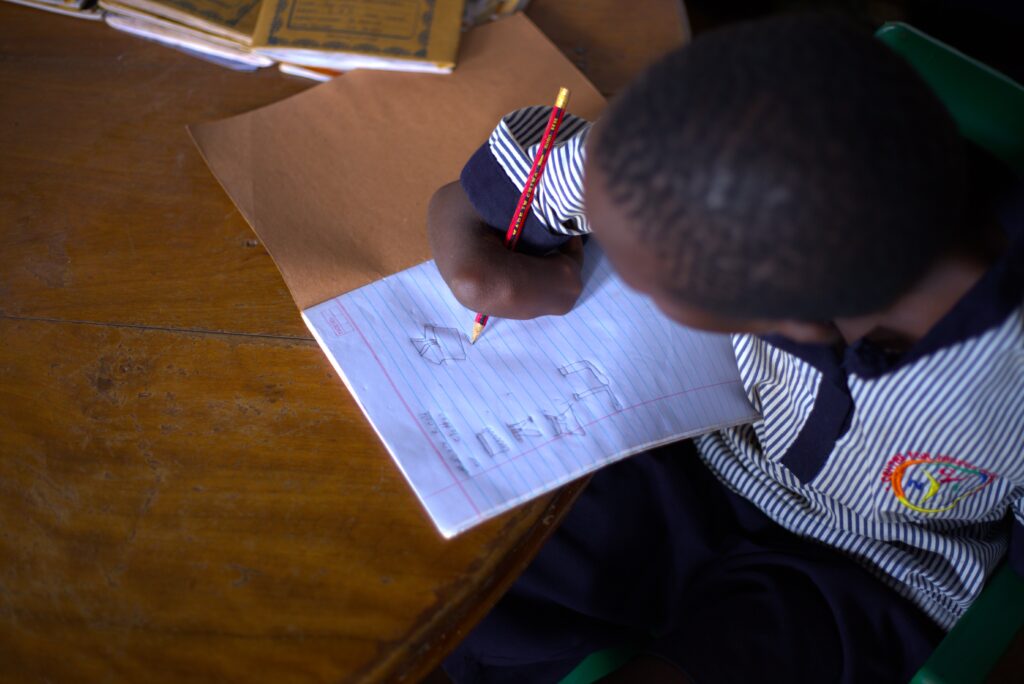

A special needs child does class assignment at the Wisdom Hub school. Photo by Moses Sserunjogi.

Driven by the mission of cultivating, and nurturing an inclusive environment for every child to thrive, the Wisdom Hub Nursery and Primary School operates on a model where children with special needs are enrolled alongside those abled differently to learn in the same class as their support system.

In the classroom, the children are taught to embrace diversity “as a way of developing a community that looks at people equally despite their conditions,” according to Walusimbi.

Walusimbi opened doors at the Wisdom Hub in 2013 and has seen over 300 children that have crossed into secondary school despite their disabilities such as autism, cerebral palsy, limb length discrepancies, hearing impairment, and other physical challenges.

These children here hail from diverse regions across the country, including the central, northern, western, and eastern areas.

Ronald Mumbere, a third-grade pupil at the school hails from the Southwestern district of Kasese with a condition called limb length discrepancy, where one arm is shorter than the other.

He had required special assistance which he could get in his home district. At the school, he has received the support he needs and an enabling environment.

“Being here feels like being at home. I’ve learned to shade, numbers, writing, and reading. My friends lift me onto the swings and help me play. Whenever I ask for help, no one refuses to assist me with my work. They patiently discuss areas I haven’t grasped yet. They also make sure I get my breakfast and lunch,” he relates.

Moses Walusimbi engages learner Ronald Mumbere. Photo by Moses Sserunjogi.

Sophia Nabakiibi, is among those who study alongside children like Mumbere. She notes that there’s no distinction in sharing with children who have special needs because “we are all children, and they are my friends.”

“I share everything I have with them. I give them my pens, pencils, and books, and help explain anything they didn’t grasp well in class. During lunchtime, I ensure those without hands receive food so we can all eat together and return to class,” she shares warmly.

Lawrence Mukiibi, the Dean of Studies at the school says apart from allocating extra time they provide learning aids such as flashcards, offer tangible examples relevant to the child’s experiences, and encourage the creation of picture stories to enhance their cognitive abilities and comprehension in class.

Learner Ronald Mumbere is supported by a classmate to write his assigment. Photo by Moses Sserunjogi.

Assessing the overall school performance, Mukiibi deems it “good.” He observes that students without special needs generally outperform those with such requirements due to their circumstances.

Bugoosi explains that children with disabilities, particularly those with hearing impairment continue to perform poorly because of limited vocabulary used in learning which makes it hard for them to compete academically.

“You may find that one sign means three words, for example, the driver is driving a car. The sign of the driver, driving, and a car are the same. So for the child to improve academically, the vocabulary needs to be improved,” she says.

However, she highlights the ongoing improvement in the 2007 dictionary used by these children.

Teacher Agnes Ninsiima speaks to Solutions Now Africa reporter Rhonet Atwiine. Photo by Moses Sserunjogi.

Despite these ongoing issues, Mukiibi emphasizes the importance of resilience as teachers, particularly when dealing with the unique behaviors of children with special needs.

“Besides their learning pace, there are instances where their actions may seem unconventional. For instance, they might laugh out loud or repeat after me during lessons. In such situations, it’s crucial not to react with frustration or punishment. Instead, we embrace their contributions and find ways to engage them positively in the classroom,” he explains.

Aside from education, the school offers tailored assistance to children with disabilities through various intervention programs. These include nutrition initiatives for those facing malnutrition, therapy sessions including physiotherapy, speech, and occupational therapy.

However, as the school makes an effort, the odds against the implementation of an inclusive education are diverse and need a complete system reexamination.

Wisdom Hub Headteacher Julius Kazibwe for example notes that the current school curriculum is not designed to accommodate the pace at which children with special needs adapt to learning.

“Providing them special attention in itself may slow down the implementation of the school curriculum and therefore requires necessary adjustments to ensure that all learners are incorporated,” he says.

Wisdom Hub Headteacher Julius Kazibwe. Photo by Moses Sserunjogi.

Bugose explains that all this will be addressed in the policy that is specifically being designed to promote inclusive education and education for all special needs children. Currently, the policy is at the cabinet level, and yet to be approved.

“When it gets approved, we shall design an implementation framework and we believe that this will change the landscape of inclusive education in our country.”

Slow as it seems, for Nasirunda, the approach has offered her daughter an opportunity to reimagine life as a child and make much of it.

“Being in a school where she interacts with children of all abilities has been beneficial. She has learned to adapt quickly, improving her communication skills, and mastering household tasks such as sweeping, cooking, washing dishes, and mopping. Most importantly, she’s gaining confidence in herself with each passing day. I’m proud of the young woman she’s evolving into,” Nasirundi remarks.

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .