'Cultivating a Cure':

Communities Act Against Hunger and Malnutrition in Uganda and South Sudan

Written by: Shadrach Bethel Afaayo and Denis Okeny.

Written by: Shadrach Bethel Afaayo and Denis Okeny.

A group of mothers gather to share learnings on how their recently planted gardens are performing in the remote villages of Panyagara, in Uganda’s northeastern district of Kotido. “We all planted in anticipation of rain, and I want us to advise each other on how we can manage the flooding,” Agness Lomela, the group leader stated as she opens the afternoon meeting.

They are part of a neighborhood support system that is building synergy among mothers who aim to increase food production and raise healthy children. In their clusters, the mothers have decided to stick to a traditional food production initiative as a way of responding to the unending hunger and malnutrition.

In this system, the mothers collect organic seeds like millet and sorghum, thought to be drought resistant and distribute them among themselves. Among the seeds are also different varieties of legumes and leafy vegetables. “We have seen that our traditional crops can bear the long periods of drought and even when the rains come late, we shall still make a relatively good harvest,” Lomela said. To support the multiplication and distribution, each recipient is mandated to grow and bring back twice the amount given to them during planting.

“This is what our grandmothers have always done. However, this practice has died among us. But bringing it back has helped to reduce hunger and diseases especially among children,” she said.

Likewise, in neighbouring South Sudan, Bol Ayak, a community social worker and volunteer is assuming local heroism for the children in the communities of Ombaci Payam in the restive Yei River State. Once a week, Ayak volunteers to travel over 160 kilometres by motorbike to Juba Teaching Hospital, the capital of South Sudan. Here, he can meet health workers and share the progress report of children in his community.

A recent study showed that only 18 of Yei River County’s 40 health facilities are functional. However, they lack some basic services such as drugs, personnel and bed capacity to handle the needs of its people who are mostly displaced by war.

At Juba Teaching Hospital, health workers rely on Ayak’s report to determine the supplies needed by the children. Ayak then takes the medicine, food rations, and recommendations back to the community. “I usually receive around 20 mothers daily at my home as early as 5:30 a.m., waiting in my compound for attendance,” he said.

The model is simple. After receiving the cases, mothers and other community members mobilise for fuel to support his movement to the city hospital for the treatment and food rations.

“The community members always contribute some fuel for me to put in my bike to ride every Monday to go to Juba Teaching Hospital to secure this food stuff for their babies. I am not being paid, but it’s just the love for children and the experience I have that gives me the strength to carry on this task.”

Beyond the medicine and food supplies, he is mobilising communities to build capacity to manage feeding patterns for children in the community through backyard gardening. “The mothers are now adapting to backyard vegetable gardens to improve the quality of meals especially for children,” he said.

High malnutrition levels in South Sudan and Uganda

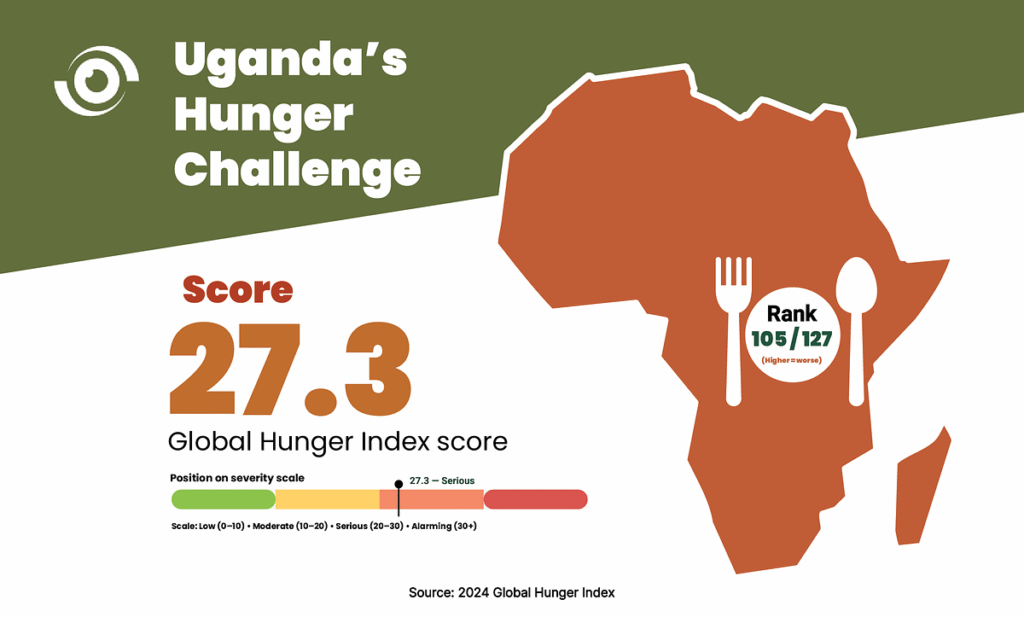

Both South Sudan and Uganda continue to face worrying levels of malnutrition, though at different scales. In both countries, the public healthy infrastructure has yet to provide an effective solution to this challenge.

Kotido for example, is in Uganda’s semi-arid northeastern region of Karamoja which has long, been synonymous with prolonged dry spells and hunger. In this region, shifting weather patterns, marked by unpredictable rainfall, longer dry spells, erratic rains, and flooding have disrupted the farming calendar and undermined crop performance.

“We used to have a defined weather pattern despite being in a dry belt. Previously, we knew the patterns of rain spread throughout the year. But this has faded and affected the output of farmers especially in the last five years,” said Benard Okuda, the Kotido District Production Officer.

According to the Nutrition Situation Report released in December 2024 by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, about 32.4% of children are underweight. The United Nations Childrens’ Fund (UNICEF), also report that more than 1,000 children under-five in the region are admitted to Moroto Referral Hospital with severe malnutrition. As the largest public health facility in Karamola, Moroto bears much of this burden. Yet, malnutrition is not confined to semi-arid Karamoja alone, even though it remains the epicentre. National data shows that one-third of children under five are stunted across Uganda.

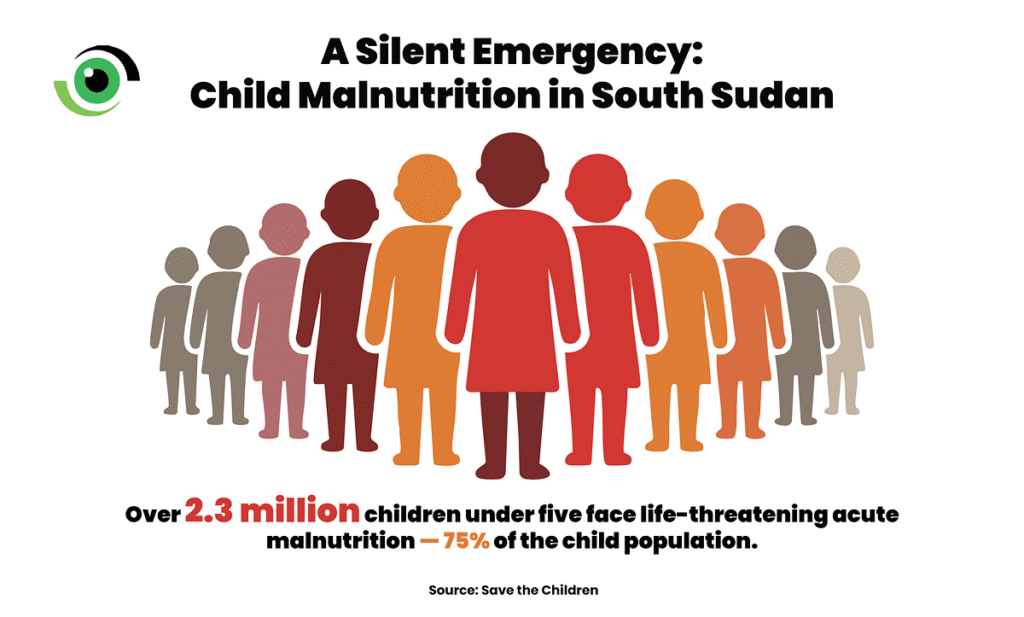

In South Sudan, it is no different. A recent report by Save the Children noted that over 2.3 million children under the age of five are facing life-threatening acute malnutrition. This figure represents 75% of the total child population in the country. South Sudan, a country facing constant conflict, currently ranks 7th among Africa’s poorest nations, according to the 2025 World Population Review Survey. Citizens have criticised the government for prioritising military spending over critical issues such as child malnutrition.

Mothers’ Mental Health Strained by Food Insecurity

In Kotido, Uganda, the welfare of the children has taken a drastic toll on mothers of malnourished children. A 2024 report from Strong Minds, a non-profit organisation which treats depression using Interpersonal Group Therapy (IPT-G) facilitated by lay community health workers, shows that the unpredictable weather patterns that affect food production, health and livelihoods are accounting for increases in depressive disorders especially among women.

“For most mothers, the pressure to feed their families is real and it mounts a degree of stress,” Specioza Kifunga, the district programme coordinator of Strong Minds Uganda explained.

In the report, the organisation noted that most mothers signing up for group therapy sessions are victims of the changing weather patterns that have shifted food security and raised threats to feed families.

Lack of comprehensive system compounds the situation

Health facilities in Kotido, including the General Hospital and Health Centres, often lack sufficient resources and equipment to provide adequate care, particularly in emergencies. The Ombach Payam community, which also hosts internally displaced persons (IDPs), is served by Lureke Health Centre II, a lower-level health facility that struggles with understaffing, low bed capacity, among other things.

Ayak, without any training in nutrition and caregiving, must take records of the state of health for the children and deliver it to Juba teaching hospital to inform nutritional recommendations and prescription.

“I do have some small knowledge in detecting malnourished children that I got from Uganda while at the refugee camp during my stay in 2016,” he explained, adding that the efforts have shown results because “many children were brought to me here for testimonies as part of achievement on the little support they got from me.”

To Betty Lula, a mother of two, Ayak has helped to seal the gap that had cost the community many children at a time the government infrastructure was not working.

“I am so happy for the efforts of Ayak. We have learned something very important, that children must be taught to eat on a timely basis, something that some of us took for granted. I have seen improvement in my children in the last six months,” she says.

Despite these two regions being separated by borders, Uganda and South Sudan are united by something common and that’s the resilience they show in the face of the challenges. Whether it’s through women multiplying drought-resistant seeds in Uganda or the selfless volunteer who has opened his home to the community and rides for kilometres weekly to collect food rations, these communities are refusing to surrender to hunger and malnutrition.

Both communities are defying the unfavorable climate conditions, political instability and limited resources to protect the health and the future of their children.

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .