Beneath the wide branches of a shade tree in Kanawat-Kotido district, a group of women sit in a circle. They gather here every week for an hour, meeting not just as neighbors but as people that have overcome loss and grief. For many, this tree has become more than a shelter from the scorching sun, it is a refuge for healing.

The women who sit here carry heavy burdens. Some face one of these struggles, others all three. Their stories differ, yet they are bound by the same invisible thread–loss brought on by a changing climate and the collapse of their farmlands.

Over 6 weeks, they return to this circle, here, under the tree,they find shelter from the sun, a refuge for their minds and the will to live again.

What’s your burden?

Each session begins with community facilitator Lomala Agnes asking the women a simple but weighty question. “What is your burden scale?

At the start of each session, community facilitator Lomala asks her group members to share how they feel. Using a pictorial scale of a woman carrying different loads, they each point at how heavy their burdens feel. Their answers reveal lives fractured by hunger and abandonment.

A mother explains that her children left home in search of food. A wife recalls how her husband abandoned her for another household that still had harvests. A 17 year old girl describes how she became a mother too soon, believing it was her only escape from hunger.

The sister who has lost her childhood because she has to work odd jobs to sustain her family, A widow, her voice cracking, shares how she lost both her husband and her cattle to the drought.

One by one, the women lay down their grief, and the shade tree holds them all.

Women share with each other in an intimate conversation

The land has betrayed them–It refuses to give back the seedling that it was given at the start of the season, the sky has turned its canvas against them–the rains are late. Once again like it has done many times, it has closed leaving their hearts and minds with unease.

Achii pays attention to Lomala as she explains what mental health burdens are

One of the newest members is Achii Rose, a farmer in Kotido West division and mother of four.

“My husband left with another woman because we had no food this season,” she says quietly. “I was stressed seeing my children wither from hunger, and still the rain has refused to come.”

Five years ago, Karamoja endured one of its worst droughts. Recovery has been painfully slow. For Achii, last season’s crops failed completely. With no seeds left and no harvest, she slipped into isolation.

“She kept to herself,” recalls facilitator Lomala. “Here, we are a communal people, so when someone withdraws, we know something is wrong.”

A neighbor invited her to join the therapy group. Now, in her second week, Achii sits beneath the tree listening closely. Her pain is still raw, but she no longer carries it alone.

Achii seen at her house.

With five people to feed, an abandoned, and withdrawn, Achii was diagnosed with depression as a result of life change.

My husband’s abandonment in favour of the first wife was my breaking point. I had stayed strong till he walked away, opting to join the other wife whose situation was not as dire as mine–He called me Lazy and all other manner of insults. Achii sighs, holding back tears.

The Land betrayed them

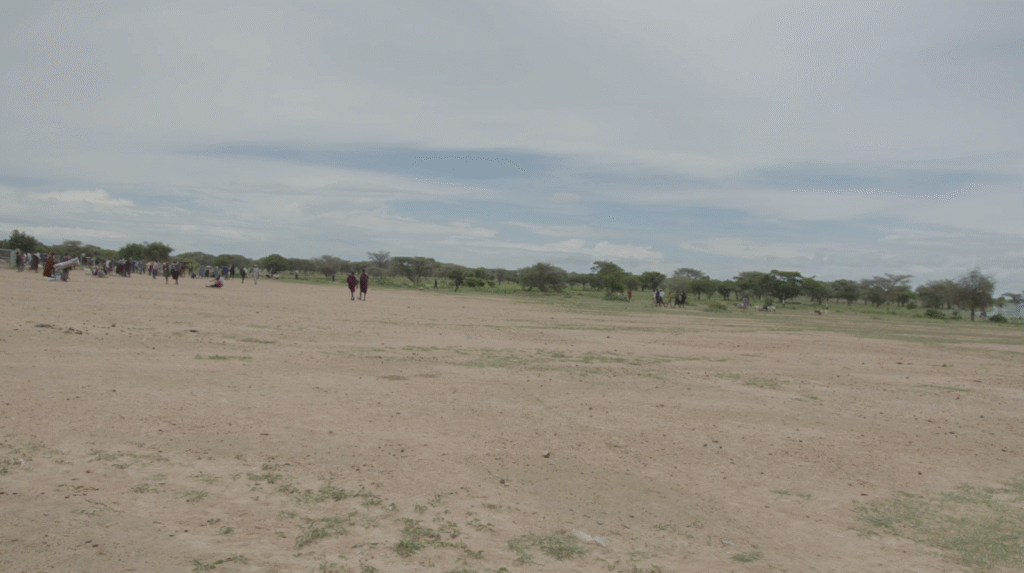

A dry land in Kotido district.

All around Kotido, the evidence of climate change is unmistakable. The seasonal rivers have dried into sand, and the soil is cracked and stubborn. The people remember when rains came faithfully each March all through to August, but now they arrive late, sometimes not at all, or in sudden floods that wash away seedlings.

A seasonal river that has run dry because of long spells of drought.

Kanawati weekly food market is now an empty expanse with a dozen of traders.

On a weekly market day in Kanawat, a space that should be filled with thousands of people and their goods, looks empty. In better years, the market would spill over with sorghum, millet, beans, groundnuts, fresh vegetables, wild fruits, and rows of cattle, goats, and chickens.

Now, most of that has vanished. A handful of grain sellers guard small piles of beans and sorghum often imported from Acholi and the few cattle tethered in the heat draw little attention.

The market day at Kanawat

The once-bustling marketplace has become a skeleton of itself, stripped down to scarcity, where even traders admit they come more out of habit than hope.

Children take produce to the market for sale.

“Most of the grain comes from outside Kotido,” explains a collections officer at the municipality. “The locals have nothing to sell. Many are in their gardens, hoping the rains come soon. But hope alone doesn’t fill an empty stomach.”

Given that the land is hard, cattle makes it easier to plough

Even for those preparing their fields, the land resists. Hard, dry, and unyielding, it takes the strength of oxen to break it. Farmers press on, praying for clouds, though the skies remain stubbornly clear.

Seedling or food, choose your poison.

“These beans I bought at the beginning of the year,” one woman explains, sitting beside her pile. “I planted some but they died. I kept the rest, waiting for rain that has not yet come.”

Now she sells them at double the usual price. It is not just food she is trading, but the last of her seed.

Across Karamoja, granaries that once held reserves for lean seasons now stand empty. Now food crops are bought at inflated prices, double the cost while their own gardens lie barren. With no seeds left to plant, each season begins with loss already written in it

An empty granary, a signal of food insecurity for most Karimojong households.

For women already struggling to keep their families fed, the uncertainty of the land deepens both their hunger and their despair because whether they choose to plant or eat, the future feels like it has already been stolen.

When Cattle leave

Beyond the markets, pastoralists lead their herds across vast stretches of the semi-arid savannah searching for water sources scattered miles apart and pasture barely able to feed them.

The men leaving with the herd has become a cycle of absence. They travel hundreds of kilometers, to other districts sometimes crossing into Kenya or South Sudan, chasing shrinking grass lands. Some return after months, others after years. Some never come back.

“You can spend months, sometimes a year without seeing your husband,” one woman explains. “They go far with the cattle, and you don’t know if they are alive or dead.”

At the kraals where men camp with their cattle, life is stripped to survival. Food is scarce, violence is common, and raiding is both a threat and a temptation. Young men, once raised to be protectors, now face constant risk–of ambush, disease, and despair.

Cattle are not only wealth in Karamoja, they are identity, survival, and pride. When one’s herd dies, families unravel.

“When the cows die, the men feel they die too,” explains an elder. “Without cattle, there is no dowry, no respect, no manhood. Many return broken, ashamed, turning to alcohol or abandoning their homes altogether.”

The burden then doubles for women who are left behind to raise children, manage empty fields, and endure stigma when husbands do not return.

“We lost our cattle during the drought five years ago,” recalls Namuge Lucia, another woman in the therapy circle. “Since then, I have battled depression and even thought of ending my life.”

The men, too, are caught in silence, unable to voice their pain in a culture where vulnerability is seen as weakness.

Pools of water are spread across the district and they serve both humans and animals

The sky has mood swings between floods and drought.

In Kamor , 24 kilometers from Kotido West Division, a farmer stands in a flooded garden, her seedlings ruined. Months later, the same fields lie parched and cracked.

The contradictions of climate change are cruel. When the rain comes as expected, it sometimes sweeps through too violently, turning small gardens into rivers of mud. The seedlings?, buried and drowned. Weeks later, the same plots crack under relentless heat.

A leafy vegetable garden.

For women like Achii, each season is a gamble. The granaries are empty. The fields are unpredictable.The remnant seed gone with the hope leaving a hollow emptiness of hunger,stress, despair, and anxiety.

A farmer wades through her corn garden which has been infested by army worms due to drought.

To survive, women forage for survival, gathering amaranthus, bitter leaves, and firewood. Some sell what they collect for a few shillings to buy basics. Others drink cheap alcohol to dull the ache of an empty stomach. Each day is a battle between necessity and exhaustion, hope and resignation.

A mother carries vegetables on her back.

“I pick dodo (amaranthus) and bitter leaves,” one woman says, balancing her bundle. “Sometimes we eat it, other days I sell it to afford basics like salt, food is scarce.”

She tipsily adds “alcohol is cheaper than food and helps you forget, but who forgets the burn of an empty stomach,”

A bundle of dry wood which serves as cooking fuel.

A Community Solution -Picture of therapy

A signage of Strong Minds Uganda, the organization leading the treatment of depression through talk therapy in Kotido district.

In this district StrongMinds Uganda’s group therapy model offers a lifeline. For 12 weeks, women gather under the tree, guided by community trained facilitators and mental health officers.

They learn to recognize symptoms of depression, share coping strategies, and support each other beyond the sessions.

Here, under the shade of the tree, these women return week after week. They come burdened with grief, with empty hands, with empty granaries. But in speaking, in listening, in naming their despair, they begin to reclaim back part of their lives.

A talk therapy group in session.

“In this group, we remind each other that we are not alone,” says Lomala. “We cry together, but we also laugh together.”

Story is supported by the Rosalynn Carter Fellowship, and through a partnership with Strong Minds Uganda.

Contributors

Prossy Nakomol- Transcriptions

Amos Desmond Wambi- Editor

Jeremiah Mukiibi- Photography

Kifunga Specioza Nawal- Research, and Translations.

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .