Faith Kamanzi peddles her sewing machine with detail and quietude. Her stall, situated in a corner amidst a sea of other machines is never free from thrilled groups of work colleagues fumbling with gestures.

Kamanzi is deaf. But at 23 her craft in garment selection, construction, and modification among others has earned her popularity at Kampala’s biggest retail hub, St. Balikuddembe market.

“I got a hearing loss at the age of five after a string of illnesses … the children I used to play with found it hard to live around and play with me. But my family was supportive,” Kamanzi explains through an interpreter.

But as our conversation gets deeper, my attention is drawn to a scatter of paper under her seat.

“I write on paper to be able to communicate with most of my walk-in customers … they struggle but later catch up because they are sure that I can deliver on their desires. Most are recommendations from other clients I have served before, and come ready for this style of communication,” she says with relish.

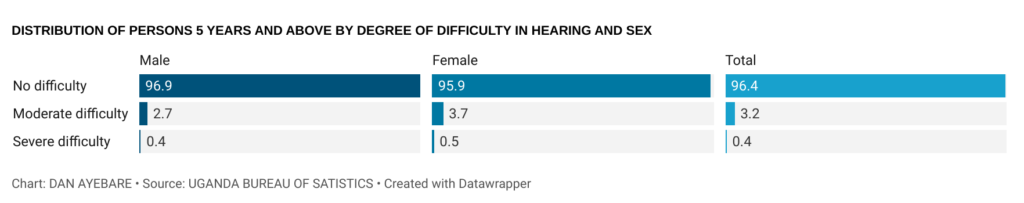

The Uganda National Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) says about 1.4 million people live with hearing impairment according to the last national census and are one of the most excluded minority groups in the country.

Activists at the Uganda National Association of the Deaf (UNAD) add that 87% of them find hardship in engaging in economic activities like business or even jobs and access to social services because of communication barriers.

Faith Kamanzi at her stall at St. Balikuddembe market in Kampala Central Business District.

Anchoring hope

Uganda was the second country in the world to adopt sign language in its laws in 1995 and Uganda Sign Language (USL) is recognized as an official language. However, teaching and extending USL to potential learners has stalled due to resource constraints.

Experts have also argued that access to education for the rural deaf remains poor.

According to UNAD Executive Director Robert Nkwangu, there is a need for a concerted effort, and well-structured approaches to accelerate and usage of USL, and the deaf community must be at the center of this innovation.

“Innovations started and owned by deaf people themselves are important because they are inspiring in their nature and can be good rallying points for social inclusion,” Nkwangu notes.

Kamanzi says the deaf community has seen initiatives from the civil society and individuals that have propagated the welfare of the deaf, including entrepreneurship, education, and skills development, of which she has been a direct beneficiary.

“I learned fashion and tailoring from a deaf-sponsored opportunity and it has drastically changed my life. And there is so much more that we are getting proud about,” she says inviting me to dedicate a day to walk me around.

The church and the café

We start at Namirembe Cathedral, the provincial headquarters of the Anglican Church in Uganda for a Sunday service.

The church has dedicated its Centenary House located on the lower terrace to the deaf community for Sunday prayers, where Kamanzi is a drummer.

However, there are only two others in Kampala; St. Francis, Makerere and St. Peters in Ntinda, a Kampala suburb.

“The churches are very few and too distant from people’s settlements, but the fact that they are growing is progress in itself. A church is an institution where people trust in all circumstances. Deaf people have a lot of problems like unemployment and discrimination,” Reverend Paul Sajjabi the Vicar at the Signs Language church said through an interpreter.

After the Sunday service, Kamanzi’s favorite hangout spot is Silent Café about a kilometer away from the church. The popular eatery is an innovation of the deaf for the deaf. Congregants gather here after the church service to enjoy to wind off the week.

It was started by Nasser Ssenyondo in 2019, as “a public statement on contemporary inclusion”.

“This place is a statement. Everyone in this community knows that it is a deaf people’s space and that means that whoever passes around here will think about the subject of inclusion. There are many people who come to eat here when they are not even deaf, but they come to see what goes on and they later become ambassadors of inclusion,” Ssenyondo says.

Silent café’ is very famous for cost-friendly Pizzas, Ice-cream flavors, and a bevy of cuisines all made by deaf people. Sign language illiterate customers are aided to communicate using a chat.

The chat can really be humbling and helps people to sync into a world where everyone else in your environment does not understand what you say.

“This place helps you to get into the world deaf people traverse daily in a contemporary world. When you talk of inclusion, people think the people with disabilities are begging for mercy and empathy,” he says

The signs Tv

As he explains, Ssenyondo points at a screen where a sign language bulletin plays repeatedly for every group of clients who walk in.

A new digital content platform has been pioneered in the country to cater to people with hearing impairment.

Signs TV curates sign language content and ousts an episode every week, to help the deaf communities catch up with news that has made rounds on mainstream media.

It has been pioneered by Suzan Mujawa, a renowned signs interpreter.

“Deaf people miss out on the key news national issues and events,” she says citing a controversial situation in which a man with hearing impairment was shot by security operatives for allegedly defying a dusk to dawn curfew during the covid-19 pandemic.

“As I always presented news on TV a sign interpreter, I would get feedback that the window for signs is so small. The deaf people would tell me that they hardly can see what I sign. That always hurt me because I felt I was not delivering on my job,” Mujjawa explains.

On this channel, Mujjawa purposes to produce content with a full screen covering sign language anchors. The first growing channel also produces entertainment shows and talk shows in sign language.

After such an ‘inclusive Sunday’, Kamanzi returns to work on Monday morning, well aware that she has a community where she belongs and is appreciated.

“Loneliness is the basis on which all people can get depressed just like the deaf. I must say I felt no one cared before I discovered these places. At church, I am now a leader, I counsel others. At this cafe, I am sure every Sunday afternoon, I will meet my friends. This sometimes makes you forget that you are even deaf. I am a happy person,” Kamanzi caps it off.

In Kamanzi’s world, protecting and codifying their Sign Language, herself and other deaf people have unified their community. Some scholars insist ‘Disabled’ as a label shouldn’t be used to refer to deaf people.

Recent News

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .