On a humid afternoon in Kasawo, Mukono District in central Uganda, 43-year-old Kisekka Abubaker carefully scoops a handful of fermented cocoa beans as he explains their journey from the garden to the drying tarpaulin.

He has tended cocoa trees since 2015, devoting two and a half acres of land to the crop, which is one of Uganda’s foreign exchange earners.

Despite producing the raw material that powers a global chocolate industry worth over $100 billion as valued in 2024, he can count the times he has tasted chocolate in his life.

“For years, we planted and sold without knowing where it goes or why,” Kiseka says, standing among neatly spaced cocoa trees. “We just knew that if it pays, it’s okay,” he adds.

He is not alone. Another farmer, Bukenya Siriri, says “I can go a whole year without tasting chocolate.”

For smallholder cocoa farmers in Uganda, cocoa by-products remain a luxury which the earnings from their harvest cannot afford them. Beyond chocolate, farmers explained that cocoa can also produce wine and juice yet many farmers are still disconnected from these opportunities limiting their share of the cocoa economy.

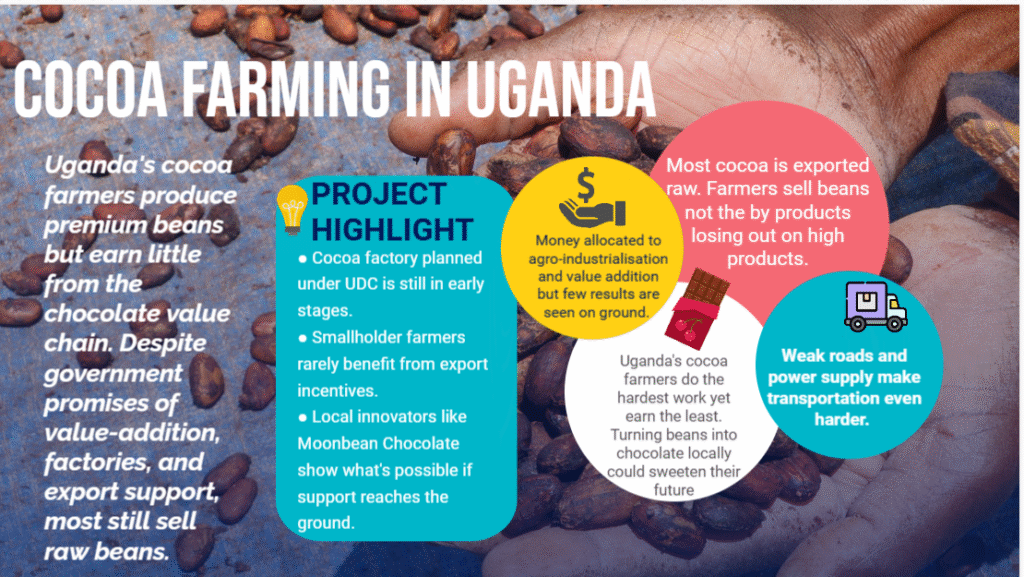

The country exports largely raw beans into the global chocolate industry, which forfeits the economic benefit of farmers on the value chain.

This, coupled with dependence on exploitative middlemen, and a yet to be streamlined policy on cocoa farming and value chain management in the country are working against farmers.

While the national plan for cocoa production and development promise value-addition and factories, money, machines and quality control, they are yet to reach the farm gate and farmers are left to tow the burden.

Cocoa farming in Uganda is delicate back-breaking work. From planting to harvesting, fermenting, and drying, each stage requires precision. If the pods are not properly fermented or dried, beans lose quality, and farmers lose their market.

Kiseka recalls a time when the government used to send machines and pesticides to support the spraying of pests that destroy cocoa trees. “They stopped,” he says.

“Now, we fight insects manually. The chemicals we can get are too poisonous and damage not just our own but even the neighboring plants,” he adds.

To supplement the resources to invest in their gardens, farmers sometimes convert cocoa husks into cooking fuel household use. “It burns quickly but helps us save on costs,” Kiseka explains.

Uganda earned US$341.62 million from cocoa exports last year, and currently from January to August is valued at US$502.52 million. Farmers like Kiseka sell a kilo of fermented beans at UGX 30,000–40,000 (about $12), depending on the weather and the dollar rate. Yet in Kampala, a 50-gram chocolate bar sells for around UGX 12,000.

The National Coffee Research Institute (NaCORI), one of 16 institutions under the National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO) has been leading efforts to multiply the production of cocoa and coffee in Uganda.

According to the institution’s lead researcher Job Chemutai, NaCORI, is pushing for a law Cocoa Bill, similar to the Coffee which aims to enhance productivity, improve quality, and strengthen marketing opportunities for cocoa farmers through grants and policy support.

Currently, Chemutai says the institute is using available mechanisms to see that farmers find better prices for their beans.

“Before, farmers sold beans at as low as 7,000 shillings per kilo,” Job says. “Now the average is 25,000.” Prices are set by demand and supply, but the bigger issue is access to equipment and technology.

“Equipment is expensive. Farmers need access to improved technology, and they need to be part of developing prototypes. They must know that what they are growing is big,” he adds.

Additionally, the institute is organizing farmers into groups and offering opportunities in production and value-addition training.

He also cites government interventions like Parish Development Model (PDM) funds and donor support, but acknowledges follow-up and accountability remain weak.

The global chocolate market is valued at over $100 billion, but Ugandan farmers remain at the lowest end of the chain. “We feel bad when we hear how much chocolate costs abroad,” says Kiseka. “We are the ones who grow it, but we don’t benefit much.”

In Bugolobi, one of Kampala’s affluent suburbs, Shadrach Kabenge has been codenamed “the chocolate maker”. He runs Moonbean a social enterprise which brings together the city’s chocolate lovers to experiment the making of chocolate from bean to bar.

Consumers pay a friendly sum, and dedicate time for the bean to bar classes where they learn about fermented beans from farmers, roasting, grinding, tempering, and finally wrapping chocolate bars. They are also taken through the value-chain of cocoa production to inspire cocoa farming.

Moonbean was in 2018 by James Scott Pitkeathly and his wife Denise Ferris, has since become Uganda’s largest chocolate producer, and also supports to train farmers in production and value addition.

The reason of the training is that as the biggest local buyer of beans, Moonbean says farmers are still struggling with quality control is another hurdle.

“Some farmers rush to sell beans without proper fermentation. They want quick cash,” Kabenge says adding that. “Poorly fermented beans compromise the final product.”

From Kiseka’s experience, the fermenting process has been daunting to farmers. The government through NACoRI has distributed fermenting boxes to farmers that reduces drying time from eight days to just four or five. However, the boxes require a labor stalking regular cleaning which farmers are yet to master.

“If not cleaned well, it spoils the beans,” Kiseka says. “That can make you lose the whole market.”

Still, Moonbean represents what could be possible if more of Uganda’s cocoa were processed locally: farmers earning more, consumers accessing affordable chocolate, and the country capturing value beyond raw exports.

Uganda’s ideal weather makes cocoa a promising cash crop. Yet without clear, accountable structures, the country risks repeating the mistakes of coffee where smallholders remain poor despite Uganda being one of the world’s top exporters.

According to Chemutai, producing world class chocolate for example requires a cold chain which Switzerland has perfected while Uganda still operates on a warm chain which complicates quality control.

Farmers like Kiseka are grateful for organizations like NaCORI that provide training and support. They call for more consistent government intervention: spraying programs, better infrastructure, affordable equipment, and genuine follow-up on funding.

Moonbean offers one model of transparency, sourcing locally and involving farmers in value addition. If replicated, it could transform livelihoods.

For Uganda to reap the true benefits of cocoa, however, it will require more than innovation. It will demand political will to ensure transparency, accountability, and investment in local value chains.

As Abubaker reflects, standing amid his trees: “We are proud to grow cocoa. But we want to see where it goes, and not feel like we are wasting our time. We want our children to know there is a greater cause we’re working for.”

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .