It has been two years since Daniel Walakira survived what could have been his last day on earth due to suicide.

Daniel, a 22-year-old university student was once held onto big dreams until grief spiralled him into depression which led him to attempting to take his own life.

He recalls getting a call from an unknown number telling him that both his parents had been involved in an accident and they had both died on the spot.

“There was no one to talk to. Everyone just said ‘be strong’, he recalls. “So, I drank until I blacked out on most nights,” he shares.

He would eventually end up in Butabika after an attempted suicide.

Like many others, he didn’t recognize his emotional breakdown as depression. He mirrors many other young men hiding pain behind silence, alcohol or work.

“I thought I was just weak,” he says. “But it was more than that, I was drowning inside.”

Daniel started attending rehabilitation programs to help with his decade long struggle of alcohol dependency.

“I used to think being a man,” he says. “But I have learnt that speaking out doesn’t make me weak, it makes me human.”

“I still struggle sometimes,” Walakira admits. “But I know I now know that I am not less of a man for feeling. I’m stronger for surviving and for choosing to live.”

In a country where tradition and transformation often collide, mental health is becoming a major concern.

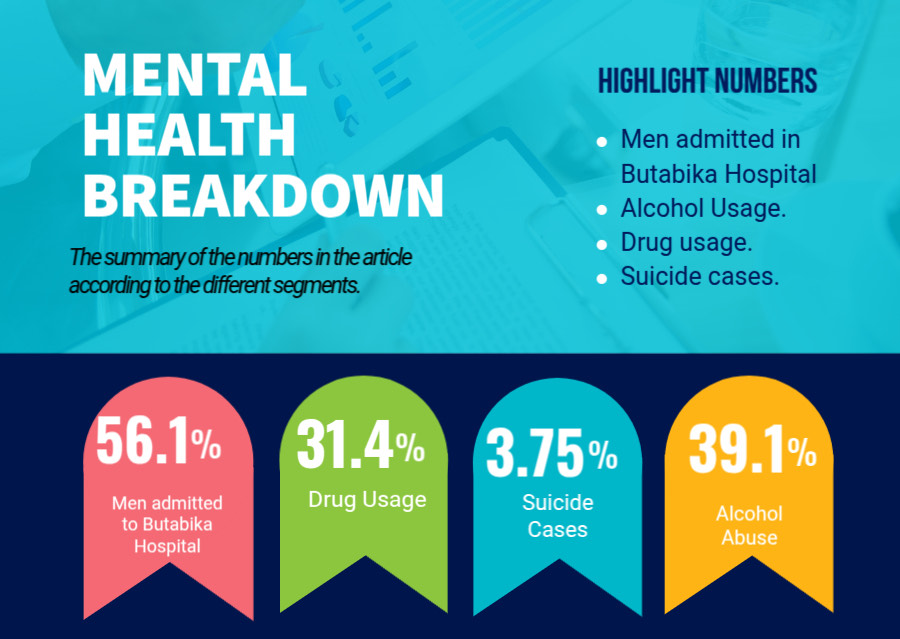

According to recent data from Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital it shows that 56.1% of the patients admitted for mental health treatment are men out of 4198 patients that are admitted.

Most of these men go to mental health units not because they sought help early but because their struggles reached a breaking point.

Some of the mental breaking points are often handled with alcohol and drug abuse since admitting to emotional distress is seen as a weakness.

National statistics reveal that 39.1% of young people use alcohol and 31.4% use drugs as coping mechanisms to deal with emotional and psychological distress rather than turning to professional help.

National statistics reveal that 39.1% of young people use alcohol and 31.4% use drugs as coping mechanisms to deal with emotional and psychological distress rather than turning to professional help.

Dr. Martin Amanya, a psychologist at Safe Places in Kyambogo says that he sees all these struggles almost on a daily basis.

“Young men don’t come to us until they are in crisis,” he explains.

“They treat the problem like a nail and use a hammer as a solution.” He goes on to say.

“These young men reach a point and they get stuck and this creates a fog in their minds and in order to clear this fog, they start drinking to “clear their minds.” says Dr Martin.

This toxic masculinity not only prevents many from seeking therapy but also isolates them.

As societal pressures mount from unemployment to social expectations, young men are left alone to battle demons they cannot name and often, dare not speak of.

Amidst the darkness, change is beginning to emerge.

Some organizations and government health units are providing free therapy to those struggling with depression and are working to create safe and stigma-free spaces for young men.

Mental health clinical psychologist who works with Strong Minds, Dr Arnold Ssazi says, “Many of these young men think they are the only ones feeling this way”.

“But once they realize others are going through the same struggles, they begin to open up. That’s when healing begins.” says Ssazi.

Strong Minds has also partnered with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to expand access to mental health services, especially among vulnerable populations.

Through these partnerships, they carry out mental health awareness campaigns, community dialogues and outreach initiatives breaking cultural taboos and challenging harmful gender norms.

One of the greatest challenges in mental health recovery for young Ugandan men is unlearning the toxic beliefs they have been taught about masculinity.

The process isn’t easy. It involves confronting years of social conditioning and personal shame. Many men must also navigate the judgment of peers and family members who still cling to traditional ideals.

While the growing awareness around men’s mental health in Uganda is encouraging, significant challenges remain.

The country has about 76 practicing psychiatrists for a population of over 45 million and over 700 mental health trained nurses but only 15% are deployed and also not in mental health units but just as regular nurses in other hospitals.

Out of the budget that is made for the health sector of Uganda, only 0.95% is given to the mental health sector.

And out of the 0.95 (which is like 1% of the health budget) and 85 of that 1% is given to Butabika Referral Hospital leaving the other regional referral units established by the government overwhelmed and underfunded.

However, even when the highest percentage of funding goes to Butabika Hospital, the unit is still overwhelmed by the rising numbers of patients they get and have to admit.

Dr. Hafsa Lukwata, the Commissioner in Charge of Mental Health at the Ministry of Health.

Dr Hafsa Lukwata the Ass. Commissioner Incharge of Mental Health at the Ministry of Health says, “Butabika is well equipped with all the medicine and high tech equipment it may need to treat patients but it is overwhelmed.”

“The hospital is meant to accommodate 650 patients but instead it accommodates over 1500 patients.” she says.

This overloading of the hospital overwhelms the hospital funds making it seem like it’s not doing its job even when it is trying.

Dr Lukwata explains that the government has established around 17 more referral mental health units in different regions around Uganda like; Mbale, Soroti, Lira, Mubende, etc and these units are helping bring mental health care closer to the people who can’t move to the city where the general referral hospital (Butabika) is located.

She adds that most of the men who frequent these units are young men between the age of 19-35 struggling with depression and have taken up alcoholism as a coping mechanism, one because the alcohol is freely available and two because they feel it’s the easiest way to escape reality.

For young men trying to find their place in a world filled with economic, social and personal pressures, the silence about what’s going on in their mind can be deadly.

And this silence leads to many opting to commit suicide just like Daniel Walakira almost did.

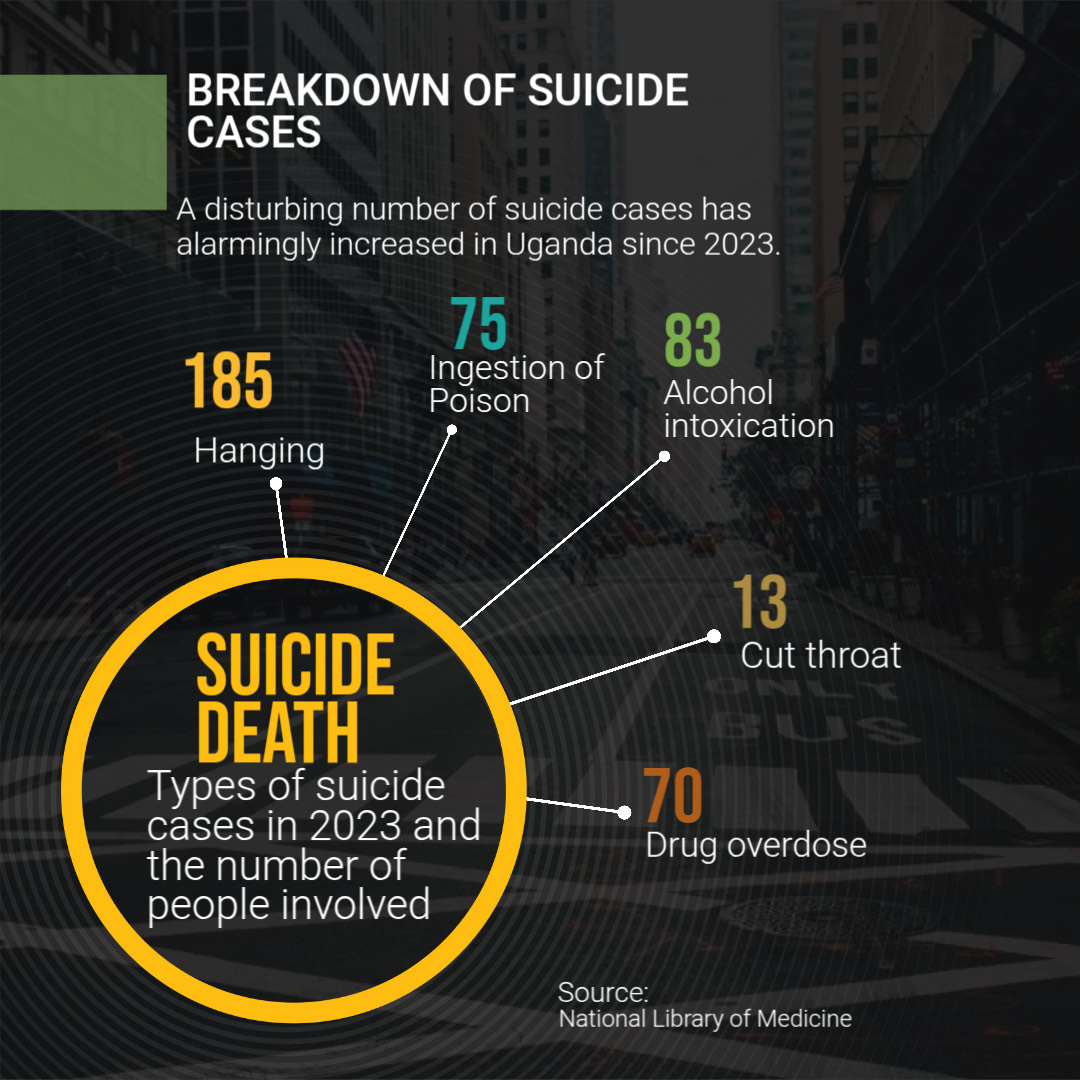

A disturbing number of suicide cases has alarmingly increased in Uganda since 2023 with males being three times more than women by 3.75 %.

The most common methods used by people are poisoning and hanging.

But one should know that there are a number of suicide cases that go unreported because of the stigma associated with suicide, mental health and the criminalization of suicide by the law enforcers of Uganda.

Mental health advocates argue that this needs to change, not only to save lives but to build a more emotionally resilient generation of young Ugandan men because having a mental illness is not a crime.

As we move forward, the country needs to embrace mental health awareness more and men need to navigate their mental health challenges more openly and freely in order to heal and grow without fear.

Recent News

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .