In the crowded settlement of Namuwongo, 17-year-old Sarah (not her real name) leans over a mannequin head, braiding its synthetic hair with quiet focus. Her hands move with skill but her eyes carry the story of a dream interrupted. At 16, while in Primary Seven, Sarah discovered she was pregnant.

“When it happened, I thought my life was over,” she recalls.

The boy responsible was only 17 at that time. Raised by a single mother in Busabala, Sarah’s world crumbled. She moved to Namuwongo with her family, searching for survival. There, she found help at Touch the Slum Uganda, a youth-led organization that rescues, shelters, and empowers teenage mothers.

“They picked me up when I had lost all hope,” she says. “Now I’m learning hairdressing and want to open my own salon. My dream is for my baby to go to school and have a better life than mine.”

Covid 19 lockdowns deepened Uganda’s teenage pregnacy crisis and while government policies stalled, many young girls were affected by this crisis which increased the high rate of mortality rates among young girls in Uganda.

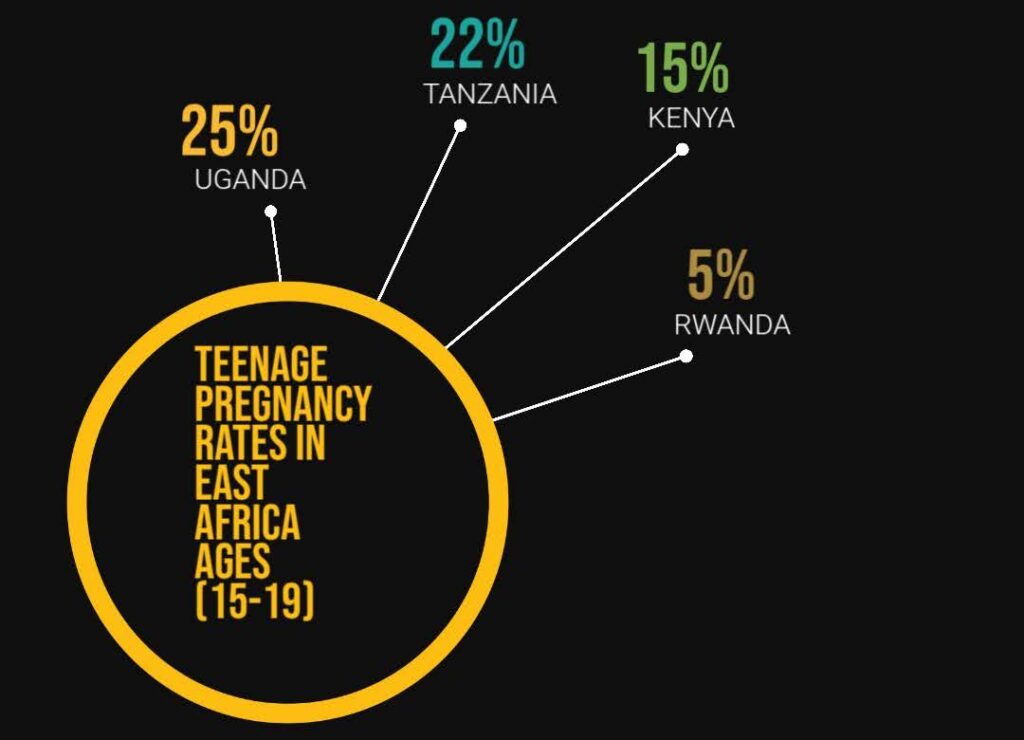

Uganda remains one of the worst-affected countries in East Africa, despite having laws and programs designed to protect adolescent girls. According to UNFPA (2023), nearly 1 in 4 girls aged 15–19 in Uganda is pregnant or already a mother the highest rate in East Africa. Each year, an estimated 300,000 teenage pregnancies are recorded about 821 every day.

Kampala mirrors the crisis with over 8,460 teenage pregnancies reported in 2021 (Ministry of Health). Most cases came from slum areas such as Namuwongo, Katwe, and Kisenyi and 25% of all teenage mothers live in urban poverty settings (UBOS, 2022).

When COVID-19 hit, Uganda’s schools closed for nearly two years the longest lockdown in the world.What followed was a silent epidemic of teenage pregnancies.

Over 354,736 teenage pregnancies were reported in 2020 (Ministry of Health), and between January and September 2021, another 290,219 cases were registered. On average, 32,000 girls became pregnant every month during the pandemic.

In Kampala, pregnancies among girls aged 10–24 rose by 22.5% and among girls aged 10–14, pregnancies spiked by 366% between March and September 2020.

“COVID-19 didn’t create the crisis it exposed it,”says Touch the Slum Uganda’s Program Coordinator Julius Wambuzi. “Many girls got trapped at home with abusers. By the time schools reopened, most of them were already mothers.”

Touch the slum Uganda a youth led organization Founded in 2020, the youth-led NGO operates in Namuwongo, one of Kampala’s poorest informal settlements. Its mission to help teenage mothers rebuild their lives through education, skills, and dignity.

“We are dedicated to providing crisis care, literacy and skills to teen mothers not just rescue, but a pathway to a self-reliant life,” says the Program Coordinator. “When we give a young mother a skill like hairdressing, we’re giving her hope, a future, and a chance for her child not to repeat the cycle.”Says Wambuzi.

When I asked about the persistent rise in teenage pregnancies despite numerous policies, Dr. Richard Mugahi, the Assistant Commissioner of Health, acknowledged that the problem is deeply rooted in social and cultural norms.

“The causes are both social and cultural,” Dr. Mugahi explained. “In some communities, once a girl develops breasts, she is seen as ready for marriage. Society still perceives girls as a source of wealth ‘kasukali’ meaning parents expect to get something out of them through early marriages.”

He added that the government, through the Ministry of Health’s Community Health Department, is working to improve implementation of policies such as the Re-entry to School Policy and the National Strategy to End Child Marriage and Teenage Pregnancy (2022–2030).

“We have a program called DICAH, which stands for District Committees on Adolescent Health,” he said. “These committees guide the implementation of adolescent health programming at district level.”

According to Dr. Mugahi, the DICAH initiative operates in about 50 percent of Uganda’s districts, bringing together various sectors including health, education, gender, and the police to coordinate teenage pregnancy surveillance and response.

“Where DICAH is active, you see a joint front,” he said. “Health workers, teachers, gender officers, and police work together to protect girls, track cases, and respond effectively.”

Despite progress, Dr. Mugahi admits that gaps still exist in districts where the program has yet to be fully rolled out, calling for stronger district-level coordination and community awareness to address harmful cultural beliefs.

Despite strong policies including the Re-entry to School Policy (2020) and Adolescent Health Guidelines (2015) implementation remains poor.Schools often expel pregnant girls, and many defilement cases are “settled” privately.

“Policies are there, but enforcement is missing,” says the NGO program coordinator. “Until government ensures these policies work on the ground, more girls will fall through the cracks.”

Uganda’s teenage pregnancy crisis is not just a moral issue it’s a public accountability failure. Experts call for funding and enforcement of policies, partnerships with NGOs like Touch the Slum, and transparent data reporting to bring about change in the society

“We call on government to ensure teenage mothers access free education, start-up capital and safe homes,” says the MR Wambuzi Julius. “Without those three, the risks stay high.”

While the Ministry of Health cites progress through DICAH and cross-sector collaborations, organizations like Touch the Slum Uganda say more must be done to ensure such policies reach the most vulnerable communities in Kampala’s slums.

© 2022 - Media Challenge Initiative | All Rights Reserved .