Uganda’s neonatal health crisis:

Survival at the edge of life

Written by: Shadrach Afayo

On a humid Saturday morning in Mbale City, the neonatal ward at Mbale Regional Referral Hospital hums with quiet urgency.

Inside a small, sunlit room, Ms. Chemutai Esther cradles her son, Harvey—a baby whose story has become both a symbol of hope and a mirror reflecting the cracks in Uganda’s health system.

Harvey was born too soon, too small, and with a fragile heartbeat that wavered in the incubator for weeks. After a month and two weeks in the neonatal unit, Chemutai finally brought him home, thinking the worst was over.

But joy turned to dread when she noticed her baby struggled to follow light or faces.

Her concern reached Dr. Kathy Burgoine, the neonatologist leading Mbale’s neonatal unit. She quickly arranged a screening with ophthalmologist Dr. Iddi Ndabawe, whose diagnosis confirmed every mother’s nightmare: Harvey had Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP)—a preventable condition that causes blindness in premature babies when not detected early.

At the launch of the Hope and Vision Programme, Chemutai’s voice trembled as she recounted her ordeal before a hall filled with health workers, donors, and policymakers.

“It is hard being with Harvey at home because sometimes he doesn’t see, and that hurts me so much,” she said, tears breaking her composure.

The Hope and Vision Programme, funded by international partners like EYESHA, is centered around promoting the early screening of Retinotherapy of Prematurity (ROP) among neonates while ensuring access to better quality treatment.

Spearheaded by Born on the Edge, the programme will also provide counseling sessions to mothers of babies born too early, in a bid to ensure that their mental health and emotional well-being are adequately addressed.

Harvey survived, but his partial blindness became a rallying point. His story inspired the creation of Born on the Edge’s ROP screening programme, now a beacon of what is possible when partnerships meet purpose.

Yet Harvey’s story also lays bare a much deeper crisis—one of underfunding, mismanagement, and a fragile health system where the smallest lives depend on the thinnest threads of care and accountability.

The fragile first 28 days

In Uganda, the first 28 days of life remain the deadliest. Nearly 45,000 newborns die each year during this window—about 40% of all infant deaths nationwide. These numbers hide stories like Harvey’s: families fighting for survival in under-equipped hospitals, mothers turned away from overcrowded wards, and babies lost to conditions that are easily preventable elsewhere.

The neonatal mortality rate in Uganda has hovered between 18 and 22 deaths per 1,000 live births in recent years. While this marks progress compared to past decades, it remains higher than the global average and far above rates seen in wealthier nations. Across sub-Saharan Africa, where neonatal mortality averages 27 per 1,000, Uganda’s numbers reflect both progress and persistent peril.

By comparison, high-income countries such as Japan, Sweden, or Canada report neonatal mortality rates below 5 per 1,000. These disparities are not biological—they are systemic. They trace back to differences in infrastructure, staffing, funding, and adherence to World Health Organization (WHO) standards for newborn care.

According to WHO, every health facility that conducts deliveries must provide basic newborn care—clean delivery, warmth, breastfeeding support, and emergency resuscitation. Higher-level facilities should offer special care (Level 2) for preterm or mildly ill babies, and intensive care (Level 3) for critically ill or extremely premature infants.

Uganda has many facilities that call themselves “NICUs,” but very few meet full Level 3 criteria—defined by the ability to provide continuous monitoring, ventilatory support, neonatal surgery, and uninterrupted power and oxygen supply. The result is a tiered system where access to survival is determined by geography and luck.

-Too few NICUs for too many babies-

Neonatal care is classified into four levels. At the most basic, Level 1 provides observation for stable, full-term infants, while Level 2 supports preterm or mildly ill babies needing oxygen or feeding tubes. Level 3 offers intensive care for critically ill newborns requiring advanced interventions like ventilation or surgery, and Level 4 represents the most advanced care available, reserved for the sickest and most premature infants.

Uganda currently has only five Level 3 NICUs nationwide, alongside a handful of mostly Level 2 facilities concentrated in Kampala’s private and not-for-profit hospitals. This distribution leaves most rural regions dangerously underserved. Mothers from upcountry districts often travel hundreds of kilometers to referral hospitals, only to find wards already running at 150% bed occupancy.

At Mbale Regional Referral Hospital, where Harvey was born, the neonatal ward was designed for 20 babies. Today, it routinely houses 80 to 120 newborns—an exhausting cycle of overcrowding and improvisation. This “beautiful state of chaos,” as neonatologist Dr. Kathy Burgoine describes it as the daily reality for health workers trying to save lives with too few incubators, ventilators, or even basic supplies like oxygen.

-A chronic underinvestment-

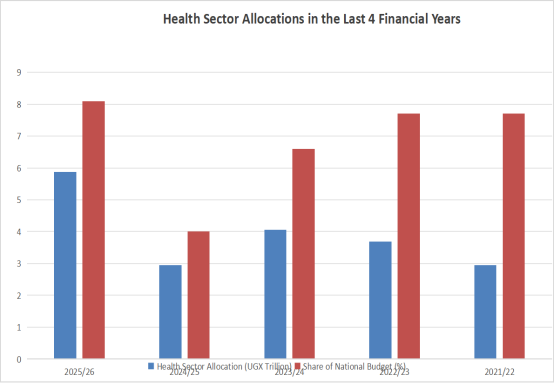

Uganda spends roughly USD 40 to 50 per person per year on health—less than half of the World Health Organization’s recommended USD 86 per capita minimum. In the 2025/2026 financial year, the Ministry of Health received Ug Shs 5.8 trillion, representing 8.1% of the national budget—an increase from previous years, but still well below the 15% Abuja Declaration target agreed upon by African Union members two decades ago.

Within that figure, neonatal care has no dedicated budget line. Instead, it is bundled under the broader Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (MNCAH) programme. This makes it nearly impossible for the public—or even Parliament—to know how much money directly supports neonatal equipment, staff training, or maintenance of NICUs.

Health facilities are legally required to display their budgets publicly so communities can monitor spending. Yet most never do. Boards meant for transparency stand empty, faded, or outdated. Without clear records, citizens cannot track whether funds intended for neonatal care are received, allocated, or spent appropriately.

Primary Health Care (PHC) grants and development grants remain the main government funding streams for hospitals. These grants are meant to cover wages, supplies, and infrastructure, but disbursements are often delayed, underfunded, or mismanaged.

Meanwhile, donor financing—through partners like USAID, Save the Children, AdaraNewborn, and the Global Financing Facility (GFF)—has filled crucial gaps, building NICUs, supplying incubators, and training nurses. But donor funding is project-based and temporary; once grants end, hospitals often struggle to sustain progress.

Alternative models like Results-Based Financing (RBF) have been piloted to reward facilities for improved maternal and neonatal outcomes. Yet these programmes remain limited in scope and have not been fully institutionalized. Without consistent domestic financing, most neonatal units continue to operate on fragile budgets—dependent on charity, faith-based organizations, or the personal dedication of overstretched staff.

-Myths, misconceptions, and cultural barriers-

Even when medical facilities exist, culture and misinformation often pull families in another direction. An estimated six in ten Ugandan mothers still give birth at home, usually with traditional birth attendants (TBAs) operating without proper hygiene or equipment.

Some newborns are fed water, tea, or cow’s milk before breastfeeding, weakening their immunity. Others have ash or cow dung applied to the umbilical cord, or are bathed immediately after birth, which increases the risk of hypothermia. Such customs, while rooted in tradition, can be deadly for preterm or low-birthweight infants.

Village elders or TBAs are often consulted before health workers, delaying critical care. “By the time babies reach us, it’s often too late,” says a midwife at Mbale Hospital. “We are fighting infections that started days earlier at home.”

Addressing these barriers requires not only medical infrastructure but also community education, trust-building, and consistent outreach. Several NGOs now run maternal health awareness campaigns to promote safe delivery, exclusive breastfeeding, and early referral—but scaling them nationally remains a challenge.

-Hope amid the chaos-

Perhaps the most inspiring example of grassroots innovation is unfolding at Mbale Regional Referral Hospital. When Dr. Burgoine arrived in 2014, the hospital had no dedicated neonatal unit despite high numbers of preterm births. Through incremental changes—handwashing protocols, nurse training, water supply improvements, and donor support—the survival rate for premature babies rose dramatically.

In 2014, no baby weighing under 1,500 grams survived. Today, survival rates for such tiny infants are steadily improving, with overall neonatal mortality at the hospital dropping from 48% to just 12%.

The latest milestone is the “Hope and Vision” programme, launched in March 2025 to screen and treat Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP), a leading cause of childhood blindness. In its first three months, 176 premature babies were screened, with 24 diagnosed with ROP. Early treatment has already prevented irreversible blindness for several infants.

The programme, spearheaded by Born on the Edge and supported by EYESHA Foundation, demonstrates what is possible when partnerships, community engagement, and international expertise converge.

-The missing link-

Despite isolated success stories, Uganda’s neonatal health crisis is fundamentally a governance issue. The underfunding of neonatal health is not only a question of limited national resources but also of misplaced priorities. Budget allocations for newborn health remain disproportionately small compared to the scale of the crisis.

Worse still, the mechanisms intended to guarantee transparency—such as requiring facilities to publish their budgets—are routinely ignored. Many hospitals and health centers operate in financial opacity, making it impossible for patients or communities to know what resources have been allocated and whether they are being used appropriately.

This absence of accountability has direct consequences. Facilities cannot reliably procure or maintain essential equipment. Ambulances sit idle without fuel, while incubators remain broken for months. Referral systems collapse under strain because funds meant for support services are either insufficient or poorly managed.

Policies restricting lower-level facilities from administering lifesaving medicines like antibiotics further expose the weaknesses in governance, leaving the most vulnerable newborns without timely care.

Even for conditions like Retinopathy of Prematurity, which is increasingly recognized as a serious threat, Uganda has yet to develop its own national guidelines. Hospitals such as Mbale are left relying on foreign protocols, highlighting a failure to translate scientific knowledge into national standards.

The absence of clear policies and weak oversight mechanisms keeps neonatal health interventions fragmented, donor-driven, and ultimately unsustainable.

-A call for political will-

Uganda’s neonatal health crisis is not just about medicine or technology—it is about priorities, transparency, and accountability. While international partners can help build NICUs and train staff, sustainable change requires political will and systemic reform.

Every Ugandan newborn deserves not only a chance to survive but also to thrive. As Dr. Burgoine aptly said at the launch of Mbale’s ROP programme: “Premature babies don’t just need to survive… they need to be able to walk, to talk, to see, and to hear.”

Uganda has the frameworks, the partners, and the community spirit to make this vision a reality. The question is whether it has the accountability mechanisms and political commitment to ensure that no child is left to die or live with preventable disability because of where they were born.